Historical Architecture of Grosse Pointe – The Tennis House

Let’s turn our attention to a rather iconic building located at 360 Moselle Place, Grosse Pointe Farms – welcome to the Tennis House. Nestled on a quiet street the Tennis House is a rather rare and fascinating building. Many people know about it, for some this will the first time they have heard of it, while others have had the privilege of playing tennis in it. It is a little piece of Grosse Pointe history that has an interesting story to tell. Tennis House photos courtesy of: Grosse Pointe Historical Society.

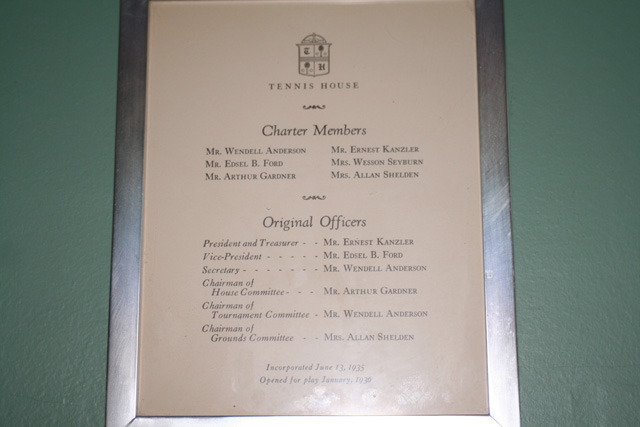

Grosse Pointe has so many rare and intriguing architectural finds, buildings that are truly special, and yet remain hidden gems. The Tennis House is one such prime example. Originally commissioned by members of the Ford family, it opened for play in January 1936 and was operated as a private indoor tennis club for over 80 years. For many years the club played host to 100 limited members, and apparently it took years to get in. Only open during the winter, reservations to play on the single clay court could not be made before 8am, and while ladies and mixed doubles play was allowed in the week, the weekends were reserved for men only. Photos courtesy of: Grosse Pointe Historical Society.

The building was built of glass and steel with a wood roof, and had the first gas fired steam boiler in the area. Source: The Grosse Pointe News, “if these walls could talk”, by Kathy Ryan. Aside from the court the building contained a lobby, a small kitchen and bar, male and female locker rooms, and a small apartment to accommodate the live-in tennis pro. Much of the interior paid homage to the classic features of the Art Deco period, which provided so much influence to the design of the building. Photo courtesy of: Grosse Pointe Historical Society.

The Tennis House was designed by New York based architect and engineer, Gavin Hadden. Born in New York, 1888, Hadden graduated from Harvard in 1910, and also earned a civil engineering degree from Columbia University in 1912. Later that year, he joined the engineering firm Barclay Parsons & Klapp. In 1917, Hadden was commissioned as a First Lieutenant of Engineers in the United States Reserve Corps and ordered into active service. Hadden travelled to Europe and was based in France as an assistant to Major General W. C. Langfitt, who commanded the American troops working with British forces to build bridges and railroads. After falling ill Hadden was sent back to the United States where he was honorably discharged in 1919.

After recovering Hadden opened his own civil engineering office in New York City, where he helped design a number of sports stadiums, such as the Philadelphia Stadium, Brown University Stadium, the Northwestern University Stadium, and the Cornell University Stadium. His specialism in this area led Hadden to write several articles and papers for architecture magazines and journals, including the American physical education review – ‘Space vs. Sports’, and ‘Stadium Design’ (published as a book in 1925).

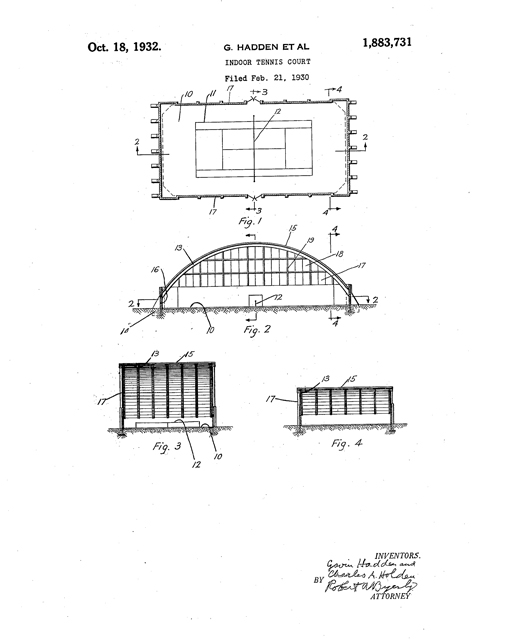

Hadden first began work on a design for an indoor tennis house in the late 1920’s. The design was the subject of a patent application for an indoor tennis court building, which Hadden filed (in conjunction with Charles A. Holden) on February 21, 1930. It was patented on October 18, 1932. It is this very design (and patent) that the Grosse Pointe Tennis House is based.

In his patent application Hadden claimed the design of the arched roof follows almost exactly the parabolic flight of the ball. His theory behind the design explains – ‘There is no waste space or waste of wall and roofing materials, since the greatest headroom extends completely across the transverse middle line, that is, the net line, of the playing surface where headroom is needed, while the roof is low all the way across the end portions of the playing surface where no great headroom is necessary’. ‘A further advantage and economy is obtained by making the sidewalls, or at least the upper portions thereof, translucent. By constructing them of glass panes eliminates the expense of clearing snow and ice from the skylights in order to permit daylight playing in the winter’. Source: patents.google.com

It was an ingenious design. And while only for a single court Hadden would later file, in 1933, a further patent (in conjunction with Charles A. Holden) for a building with a number of indoor courts. It was patented in 1936. From 1940 until his death in 1956, Hadden, a longtime civil employee of the Army Corps of Engineers, worked for the War Department, which later became the Department of Defense. He served as special assistant to General Groves, and thus was a part of the Manhattan Project from the very beginning. He aided Groves in paperwork and kept his records. He was also the official historian of the Manhattan Project. The classified Manhattan District History was prepared after the war under his editorship, and “intended to describe, in simple terms, easily understood by the average reader, just what the Manhattan District did, and how, when, and where.” Source: atomicheritage.org/

It is not clear how many of these iconic tennis structures were built or still exist within the United States. In 2016, it became apparent that it was not feasible to continue to run the facility as a private tennis club. Initial plans were to convert the structure into 12 condominiums however, it was razed in 2019, due to problems with the steel.Images courtesy of Katie Doelle.

*Photos courtesy of the Higbie Maxon Agney archives unless stated.

Written by Katie Doelle

Copyright © 2021 Katie Doelle